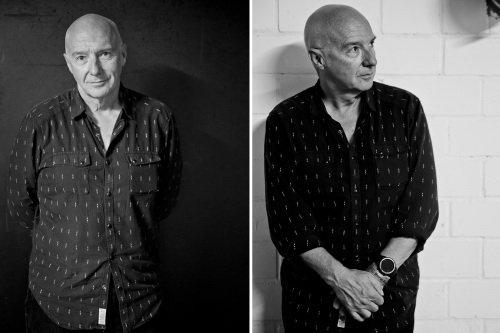

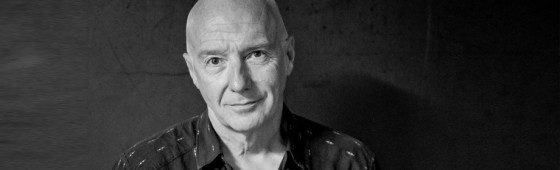

How to make a career last for half a century – Midge Ure interviewed

Posted In Interviews,Slider by Jimi Nilsson

1981 was a remarkable synthpop year with releases like Depeche Mode’s ”Speak and Spell”, Soft Cell’s “Non-Stop Erotic Cabaret” and The Human League’s “Dare”. And then we have Midge Ure’s Ultravox, with the classic single ”Vienna” (taken from the 1980 album with the same name) and the album ”Rage in Eden”.

Release’s Fredrik ”Schlatta” Wik focused on the Ultravox album ”Brilliant” and its tour in his 2012 Midge Ure interview. Now, Midge sat down with Release again, at the Amphi Festival in Cologne, for an interesting chat about his overall career and how working as a musician, songwriter and singer has changed since the 80:s.

Midge Ure shouldn’t need an introduction, not at all if you consider the projects he’s been involved in and the songs he has written. For those who came of age with a taste for the early 80:s new wave sound, then bands like Ultravox and Visage were the musical heroes, and the man behind many of the hits in those bands is Ure.

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg; he and Bob Geldof wrote the song “Do They Know It’s Christmas?”, to raise money and awareness for the famine that had overcome Ethiopia and co-organized Live Aid in 1985, one of the biggest concerts in the world. He has been awarded an Order of The British Empire (OBE) for his years of charitable work (Live Aid and Prince’s Trust to mention a few) and he is virtually a musical legend all over the world, and still some people don’t even know half of his contributions to music. Did you know he turned down an offer to become the lead singer of Sex Pistols in 1975?

A long and successful career in retrospect

After a short career with new wave act Rich Kids together with Glenn Matlock (from Sex Pistols) Rusty Egan and Steve New, Egan and Ure formed Visage together with Steve Strange in 1978. Alongside his first electronic excursion with Visage, Ure also played with 70:s rock band Thin Lizzy before he assumed the duties as Ultravox new lead singer after John Foxx left the band in 1979.

Almost immediately Ure started to write songs for Ultravox fourth album “Vienna”, including the evergreen title song. This single was the 5th most sold single of 1981, spending four weeks as number two on the British album charts and only kept off the number-one spot by John Lennon’s “Woman” and Joe Dolce’s “Shaddap You Face”. His number one came later, with the “If I Was” from his debut solo album “The Gift”. However, the synthpop scene was hardly the scene that Ure thought he would be associated with.

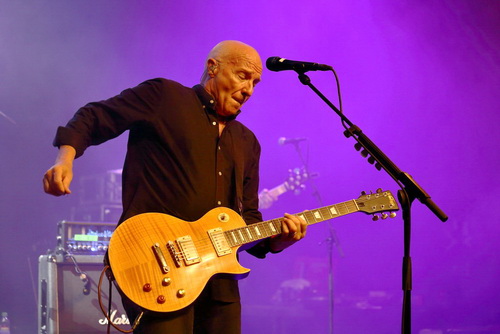

Considering where we are; what is interesting is that some 80:s artists and bands became associated with the synthpop scene because they used synthesizers. You have a broad range of fans, but you are an icon on the synth scene. Did you ever see yourself as a synthpop artist at any point in time? I guess you didn’t play festivals like Amphi in the eighties?

- I have no idea! We [Ultravox] were scared to go on stage [at Amphi] because the band who’d been on before us were [making growling sound] and mad, playing crazed goth stuff and I thought we were going to die going on there. And of course the audience sang all the songs, they knew everything! No one has told us that our music was accepted in this particular genre as well.

I never thought as a guitar player that I shouldn’t do anything, I’ve never adhered to a genre, just like in a library where that book has to go to that section and that novel has to go there. For me music is all music, it’s either good or bad, and it doesn’t really matter what the instrumentation is. The exciting thing in 1977, when I joined the Rich Kids, was to be a guitar player in the end. But hearing the music that came out of Germany in particular – I was incredibly enthused.

I loved the idea of mixing modern technology with traditional rock instruments and just see what you could do with it, and that gave birth to Visage and through Visage I joined Ultravox, so for me it wasn’t about whether I was playing guitar or whether it was keyboard, it was the odd combination and the ideas behind that odd combination that made it work.

You’ve had a long career stretching over more years than most musicians would ever dream about, and you’re not far from the 50 year mark as an artist. Tell me about your feelings when you look back on this long career – you must have done it several times – and where you are today. For instance, did you ever imagine that you would still be doing this in 2018?

- I don’t want to think about it (laugh). But no! I think that one of the main problems with the Internet is that people find old interviews where I’m saying “I don’t want to sing ‘Vienna’ when I’m thirty”, and then a few years later I read again that “I don’t want to sing ‘Vienna’ when I’m forty” – so no!

The reality is that we were the first generation of artists who went beyond being middle aged, we were the first series of artists becoming old aged – in our 60:s and 70:s – on stage still doing it. In every other genre of music that was acceptable – jazz, blues, classical and whatever. You revealed the fact that they got better on what they did. For us, we were part of that first wave of artists who were allowed to continue in what was perceived as a young person’s business. So no, I never thought I still be doing this today.

I never planned anything, I’ve never devised, I don’t plan what I’ll do next year or the year after, I just go with my instinct and have been incredibly lucky (laugh).

But still, after all these years of music production you create new albums. What is driving you to create new music? Many former artists I’ve met lost their energy and creative motivation after a while and did something completely different in their lives – families, studies, ordinary jobs and everyday life in general. What made you continue?

- I had this conversation with a few musician friends of mine recently and I think the general consensus is that we’re not good at anything else, we’re not skilled in anything other than what we do. For me it was always music.

I had a proper job as an apprentice engineer for two and half year, and I did the proper job thing and then I left it. From the moment I left it I never ever wanted to go back to it. For me it wasn’t just something where I thought “OK, I’ll do this for five years or ten years and then I’ll do something real, I’ll get sensible”. It was a career, it was always a career if I was lucky enough to be allowed to do it.

As one of the careers in life where you don’t have the choice as to whether you’re commercially popular or not, as to whether you’re relevant or not; all you can do is do what you do and the public will decide whether you’re still good enough or, in their eyes, are worthy enough carrying on doing it, and I’ve just been incredibly fortunate. I mean, it has been highs and lows. You do hit some points where you think you’re not sure anyone wants to hear anything or ever going to do it again, but then you get through that and on to the next wave whatever that happens to be.

I’ve just been incredibly fortunate that I’ve had this drive – maybe it’s a Scottish thing, maybe it’s a worker’s class thing – the drive to push yourself beyond what people expect of you.

Music has lost its value

Many artists enjoying a long career also found themselves in trouble when the music industry went through a massive transformation at the end of the 90:s. Technology’s detrimental impact on the music industry is well-documented, with global recorded music sales in decline since Napster introduced us to file sharing 20 years ago.

To access infinite volumes of music today you just need a simple subscription to a major streaming service such as Spotify, Tidal or Apple Music, and most music industry experts agree on the positive impact it has had on the overall income in the industry. In fact, it has contributed to minimise the damages of peer-to-peer networks – or much simpler, illegal filesharing. Those were the days when Napster, Kazaa and Gnutella offered free music at no cost at all – for the listener. For artists, digitization of music has been a complete disaster.

But not only have the opportunities to make a living as a musician changed, the sheer amount of music on the Internet affected the overall quality of music production. Ure explains his thoughts on this development.

Many of those artists may also have given up due to how the music industry has changed, and it has changed on a massive scale since you started your career, for instance, in how music is bought/not bought, listened to and distributed among people over the world. What are your impressions of this huge transitions of the music industry and how has it affected your career as a musician?

- I think the consumption of music has changed and I think people still need music, but the value of it has changed completely, it’s almost disposable and it’s not as well thought of as it used to be. For instance, when I was young and you wanted to buy a new David Bowie album you saved up your money, you went to the record store and you bought it, and you looked after it and you cherished this thing because you had not just invested your heart and soul into this music, you’d invested your money into it. You didn’t loan it to your friends, you didn’t take it to parties where it would get scratched and ruined – you looked after these things.

Now, because music is virtually free nobody knows what anything is anymore, people just get each other’s hard drive’s full of all sorts of music. There was a great program on the radio four or five years ago, and it was a mother talking about her fifteen-year-old son, and she asked him who his favorite artist was and he said “I don’t know” and she said “Come on, everyone’s got a favorite artist. U2? You must know U2?”, but no. She played a U2 tune and the son said “I know that, I got that on my phone!” but he had no idea of what or who – it just turned into a random number.

People don’t go and look up the specific song anymore, they just hit random and out pops a playlist that Spotify has decided that you might like. That may be the new way of spreading music because radio doesn’t do that anymore, radio used to educate people. That’s why radio back in seventies and eighties were so random so you would hear a bubblegum pop song and then you would hear Queen or you would hear David Bowie and you would hear Kraftwerk. They gave you a wide spectrum, but now it seems to be very much tunnel vision on the radio, so to get new music across to people is a really, really difficult thing.

Everything changed for the musician; recording is easy and everyone has a facility at home, everyone has a laptop and software. If you have the knowledge to do it and the time to do it, you can make a good record in your bedroom, you don’t need a big label to advance you the money – that’s changed – but it’s not all changed for the better because there is no filtering system. Everyone can make a record and everyone can stick it to the Internet but there’s no way of pointing people towards it.

But what you’re saying is that the quality of music has been affected at large?

- Yes! That’s what I’m saying! That’s the difference because there is no one filtering the quality. Back in the days you had to be spotted by an A&R guy, you had to be signed to a record label and much more – there was a filtering system. You had been chosen out of hundreds of artists, they came to you and said “OK, we can help you here”. It wasn’t always a great system but it was a system that stopped that stuff that should never had been recorded. Now everyone can record so there’s a lot of stuff out there that doesn’t really resonate.

Because of the technology, because of the amount of music that’s thrown out into the system, I can understand why people don’t want to pay for it. An entire generation of people growing up now, in their twenties and soon into their thirties, who never have purchased a piece of music, and that’s the only commodity in the world that you can do that with. You can’t walk into a shop and pick up something and say “I’m going to take that” and not pay for it, but with music you can.

And that is a huge change! Considering that, do you think we would see bands grow big in the same way as, for instance, Depeche Mode and have a long career?

- I’m not even sure you will see bands that do it solely as musicians, I think you will see bands doing it part-time. It’s so difficult for young musicians, new musicians, to make a living out of playing music. There will be part-time bands that will work during the day, they will have a job and a family, and they will take time-out to go on tour. That’s how it’s going to go which is dreadful – it’s awful – because it means that the standard of music is going to decline even further, and I don’t see how you can take it back.

I was speaking to Mark King of the band Level 42 a couple of years back and he said to me, which I thought was horrific but absolutely true, that “Maybe we’re the last generation who will do this as professional musicians because the new guys may not get the opportunity to do it”. They can still play and still do it but at a part-time basis.

But many new musicians point out that they could crowdfund a career or work with sponsors.

- I know, there are many routes for it but the reality is that if you go to a bank and want a loan to buy a car you have to have a plan, you have to figure out how you’re going to make that money to pay it back, so crowdfunding only works if you’re already famous to a certain degree. You have to have a crowd that is willing to fund you, and in order to get a crowd you have to go and play venues and in order to play venues you need to have a name, so it’s a catch-22 situation.

For many years now in America, a new band who wants to play a gig have to pay for the gig themselves. They buy all the tickets and then they have to go and sell the tickets to their friends before they can even hope of making any money, and that’s dreadful. And who’s going to sponsor an unheard of artist? You have to be notorious, slightly famous or had a little bit of success somehow before someone is going to give you the money to do that. Otherwise the only crowdfunding is yourself, just the way it was when we were kids when you had to buy your equipment, you had to go trying to get gigs and build up a little following to have a name, but without a name none of this is going to happen. It’s really, really a strange system.

Not only the way to make music, recording music, has changed radically, the way a band builds up a following has changed radically partly due to the amount of tribute bands out there. A lot of the clubs that used to be the place to take in a new band on a Tuesday, three new bands on a Thursday when the club is quiet because it helped bringing in some people to sell some beer, all of those places – all those slots – are taken up by Oasis tribute bands and Pink Floyd tribute bands or heavy metal tribute bands because they can sell more beer then, so the live situation has changed as well as the recording situation.

Making an imprint in people’s lives

Music is a fundamental aspect of many people’s lives and in some cases make substantial imprints in life-changing moments. We use music as an outlet because sometimes we just aren’t ready to confront others about difficulties going on in our lives. Music has an ability to connect with people on an emotional level, and for some people that’s enough to deal with their problems. For others music is a good stepping stone towards conflict-resolution because it relates to their lives.

For an artist to make such an imprint in people’s lives because of something they have written, it could be difficult to understand why he or she has that kind of impact, and even when you have a long career where this certainly has happened more than once it still can be difficult to get used to is.

Speaking of changes and impacts; I saw just before we started today that people want to take selfies with you and tell their stories on how much your music means to them. Some of the songs you’ve made mean a lot to many people around the world. How does it feel as an artist to have made such an impact or imprint in people’s life?

- Again, the advent of the Internet means that when people write to you they can write to you as opposed to in the old days when they had to sit and write a letter and send it to a manager or a record label, and more often than not you never saw what people said about your music.

On the Internet you can see exactly what people think, good and bad. And I found it really, really strange, even after I became successful, that people would write to me and tell me about things – major things – that happened in their lives, that they got through with a piece of music that I’ve written or I’m associated with; things like getting married or conceiving their children – major, major life things!

It took me a long time to figure out what I considered normal for me listening to other people’s music and moments in my life where those pieces of music were the soundtrack of what happened to me. All of a sudden I was in the position where this was happening to other people and I found that really, really strange that it would happen, but it does and it’s great.

What you really got to be aware of is when you’re writing music, you can’t take that into consideration. You can’t think that “Am I going to write something that’s really going to touch someone’s heart?”, because then you are contriving what you do to satisfy an unknown audience. You’re not writing for a handful of people who resonate with something you’ve written because they might not resonate with the next thing you write and certainly wouldn’t resonate with something you’ve contrived just to try to get that effect.

And that’s kind of interesting in contexts where you re-make or remix your old songs into something new, for instance, like you did on “Orchestrated” last year. I guess it’s those hardcore fans that are most critical when you re-work classic songs?

- I have to say I was pretty scared of ruining people’s memories. I didn’t really care if they liked the new versions or not, it was something I wanted to do, I didn’t care if they came back to me and said “That’s rubbish”, but I did care that people would come back and say “You’ve spoiled that moment for me, you’ve spoiled that forever, that’s gone now” so I was very careful of what I did with the music, and that idea was back in my mind. I didn’t change anything but I was afraid of what the result was going to be, the people saying “You’ve ruined ‘Vienna’ for me. I lived thirty years with that piece of music in my head and you have now done something else to it”.

The kind of general response it had is that I’ve taken it somewhere else, I’ve taken those songs and enhanced them somehow. I haven’t ruined the originals but made it wider, deeper and longer – something different about it and it’s acceptable.

As someone being on the scene for such a long time you still do many shows and tour frequently. While others don’t do full tours anymore you seem to add more and more shows. Is it still as fun to be on stage and play older songs?

- Yes, I’ve changed the songs! I have to still be enthused about doing it. I believe that the audience is not stupid, audiences could tell if you are painting by numbers, if you just going through the pieces, they know and they can feel it. They might not know why it doesn’t resonate with them but they know it’s not working for some reason.

When Ultravox became successful, we stopped doing everything we always did, so we stopped touring; Ultravox just toured when there was a new album, and I thought it was crazy. “We only get to go playing these songs once every eighteenth months or once every two years?”. So when Ultravox broke up I decided I was going to go back and do my first love – I played live long before I was allowed to make a record.

I don’t always love playing the old songs. I do some of the retro festivals in the UK and they only want to hear the old songs. I spoke to OMD about this a couple of weeks ago and they said “It’s great, you’re still making new music” and when you do a radio interview they say “Fantastic! Love the new album, let’s put on ‘Vienna’”, and that’s what happens. You have to either go with that a little bit and kind of understand that’s how it works in order to get some of your new stuff played, or you just give up and walk away and let them win, let retro and let mediocrity win.

You’ve got to carry on fighting even though it feels like you’re running up a down escalator, you just have to run a bit faster – that’s how it is with music. If you want to be in this industry you have to use the good and bad of what’s there.

I saw a great televised interview with Phil Oakey from The Human League and they asked him “You do some of these retro festivals where you just play the old stuff” and he said “Yeah, it’s OK, but you got to understand that doing one of those festivals pays for a new album”. There are no record labels who would advance you the money, crowdfunding might work for them because they got a big audience but if you want carrying on making new music it has to be funded somehow and singing some of the old things allow you to go and record and write new ones.

*****

The interview is over, we’re way beyond the allotted time, and Ure has to go to yet another one. One thing is quite clear after the interview; you rarely meet someone with such a long and successful career that still has the drive to continue making records and who wants to tour as much as possible. And many fans of whatever project Ure has participated in are probably grateful for that.

Footnote

In December 2017, Midge Ure released “Orchestrated” with new versions of Ultravox and solo songs, including new track “Ordinary Man”. There is no new Ultravox album on the horizon (July 2018). It is difficult to bring the members together (they all live different lives) for recordings and toruing, according to Midge.

Live photos for Release: Henric Carlsson

Interview and slider photo for Release: Mandy Privenau